Where does growth begin?

Nearly 90% of startups fail without ever releasing a product or acquiring a single customer. Where does growth start, and how do we strike a balance between survival and growth?

Startups are far more likely to die than grow.

Did you know that around 90% of startups fail without ever launching a product or getting a single customer?

A lot of us get into the startup game because of the allure of Growth. We want to be a part of a team—and part of a chart—that’s “up and to the right”.

But what does “growth” actually mean? Do we get too caught up thinking about it early on, when we should be focused on survival?

How do we achieve a balance between survival and growth, and where does growth begin?

Backstory

Over the past six years I’ve led growth marketing at two venture-backed startups (Series B, C), and I’ve talked to countless founders and operators. Important growth fundamentals often get missed.

In this short essay, I’m going to run through a few of those fundamentals. Much of this thinking informs our core beliefs at my advisory firm, Growth Element. Although my experience is primarily in B2B, parts of these lessons also apply to B2C, DTC, and other online businesses looking to significantly increase customer count.

Whether you’re gunning for your first dozen customers, leaping from 50 to 500 customers, or scaling up to 5,000+, this is for you.

What is growth?

Before we get into it, let’s define what we actually mean when we say “growth”.

Growth, in its simplest form, is doing better in the future than you did in the past.

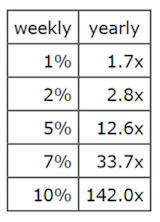

In high growth startups, growth is often considered as “the only thing that matters”. Paul Graham, Co-founder of Y Combinator, suggests that a good growth rate for an early stage startup is 5 – 7 % per week. In his essay on growth, Graham gives the example of a startup that’s making $1,000 a month and growing at 5% a week. Run the math, and that startup is growing at 12.6x yearly, and will in four years be making $25 million a month. Not bad, right?

via Paul Graham

Unfortunately, most companies will never come close to achieving that kind of growth, or, might see “good” growth rates for an unsustained period of time. That said, the type of initial business-building hurdles that “normal growth” and “high growth” startups face are often very similar.

One example is financing—more capital investment, namely angel or venture equity, might remove growth blockers (ex: headcount constraints; size/spend constraints on marketing experiments; etc.), which usually speed things up. At the same time, both bootstrapped and venture-backed startups face similar challenges around market positioning, profitability, and simply just getting customers to adopt their product.

Having more money in the bank can support growth, but money isn’t some magic wand that will bring your product to market or get your initial customers. Investment ≠ growth.

Grow fast. Grow healthy.

Broadly speaking, it’s not uncommon to achieve fast growth.

The press loves great stories of fast-growing startups and their founders. There is no shortage of communities, books, podcasts, newsletters, and other media shining a light on these stories and providing references for newer founders and operators to learn from.

But don’t be fooled—a lot of the fast growth isn’t healthy. What’s rarer, and much healthier, is when new businesses can sustain growth over the long term.

If your growth isn’t profitable, it doesn’t matter how good your metrics look in the headlines. This mode of operation will bloat your balance sheet, or worse, bankrupt your business. As mathematician and author Nassim Nicholas Taleb argues, survival is really what matters:

Growth is important, but survival is more important.

And in many cases, growth isn’t even real. I’m continuing to see this in many startups, especially as newer venture investors continue to flood the market with capital.

Mike Maples Jr., Partner at Floodgate Ventures discusses these cases as “growth theater….emphasizing growth optics over growth reality, for example….focusing on PR regardless of customer traction”. Here’s the most relevant part of what Maples says about fake growth:

“One of the primary causes of fake growth is caused by [a startup] trying to grow before it’s ready to grow.” —Mike Maples, Jr.

(via Venture Stories)

In order to survive in the early days, and thrive in the long term, startups need to be very deliberate about how and when to grow. So, again back to our question, where does growth begin?

Start hand to hand.

My friend Nathan is the founder and CEO of Sourcify, which helps thousands of companies manufacture products around the world.

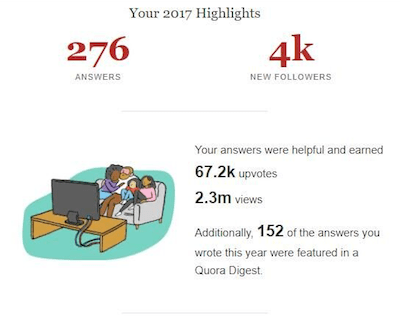

How did Nathan pick up Sourcify’s first 100 customers? By spending an hour a day on Quora, writing answers to ecommerce and entrepreneur questions. Within a year, here’s what his Quora stats looked like:

via Nathan Resnick

Can investing effort into answering questions on Quora work as a growth tactic for your business? Maybe, and that’s great. But that’s not my point here.

On the execution side, customer acquisition takes a lot of hustle—which can’t all be automated away—especially when it’s early days and you’re starting from scratch.

And with strategy, understand that the initial sprint from zero to your first 50 or 100 customers isn’t really “growth”, per se. It’s about validating your business. Again, it’s about survival.

Dave Gerhardt, CMO at Privy and host of The B2B Marketing Leaders podcast puts it succinctly:

“…the best customer acquisition strategy for a new company/product is… [to] start hand to hand….Facebook Ads ain’t gonna magically work…” —

Dave Gerhardt

Getting those initial 500 customers is a race, often up an extremely steep hill. While there are some great strategy playbooks to copy from, when you’re “pre-growth”, a lot of the winning comes down to grit and perseverance. It’s about reeling customers in and bringing them through the purchase funnel, one at a time.

Google Search Ads are often a great place to start if there’s enough search volume on relevant keywords. Reaching out to your existing network is always an important one. Cold outreach could work if done right, but warm referrals work much, much better. The channels and tactics you use when you’re racing to bring in your initial customers may not be what you’re going to scale with later on. What matters is getting the business. Get the business.

I think savvy founders often get tripped up here because they’re thinking about operating at scale starting at customer 0. They’re thinking about allowable CAC and sophistication around new channel testing and automation. In general, these are the right things to think about in growth, but should not play a starring role when you’re starting from zero.

Improve market positioning.

In addition to closing new business, you’ll also want to focus on market positioning.

To improve your chances of sustaining growth, you can leverage data from the early “hand to hand” stage to learn as much as possible about your customer, your market and how your product fits in. That includes thinking about questions like:

- Who is your customer?

- What is the pain that your product is solving, or ambition/desire that your product is fueling?

- How has your customer made buying decisions for similar products in the past?

- Which stakeholders are involved in the buying process?

- What are your product’s value propositions that really speak to your customer?

- Etc.

Hopefully, you’ll have clear hypotheses and a clear vision to build on. Being close to the customer can help you self-educate, and in turn refine your strategy. An example of using early data and a “hand to hand” approach to improve brand positioning is Foti Panagio’s story, founder of GrowthMentor.

Foti was initially quite happy with success around new user conversion metrics, but unsatisfied with user activation, and he knew very little about who GrowthMentor’s users actually were. He introduced a questionnaire into his onboarding flow, intentionally increasing onboarding friction in the process.

While hunkering down to personally review and reply to hundreds of form submissions, Foti consciously sunk conversion rates by more than 80%. But, through sacrificing lower intent users who dropped off, he was rewarded with a much stickier activation experience for the users who made it all the way through. Using the form data he was able to provide a more curated matchmaking process, which was crucial to GrowthMentor’s success as a nascent two-sided marketplace. And zooming out, Foti was able to leverage the questionnaire data to guide at least a dozen hugely important strategic questions.

Enter: Growth mode.

Ultimately, it’s up to the CEO and management team to decide when a startup is ready to go to market in a big way. There are some great resources with more formulaic approaches, but again, it’s highly individualized and comes down to an executive decision.

Characteristics of growth-readiness:

- Paying customers. A significant number of happy, paying customers.

- Signs of life on your website. Low thousands of monthly unique website visitors (preferably earned, but paid works too) that aren’t bouncing, with at least some coming through as qualified leads, however you define a qualified lead (add to cart, checkout, signup, demo booked, etc.), even if the conversion rate is very low.

- Funnel benchmarks. Your conversion rates should have some level of statistical significance, so that you can identify opportunities for improvement, make changes, and effectively measure the impact of those changes.

- Confidence around market demand for your product, and around your market positioning (even if it’s constantly evolving).

- Ideas for marketing channels and tactics that can scale your top of funnel.

- An efficient sales process to close new deals (even if it’s just one or two people and a lightweight CRM)

Requirements for growth readiness:

- A mindset shift for everyone on the team who’s involved, which at small startups usually means the entire team.

- Significant resource allocation, both in headcount and spend. Growth doesn’t happen by itself, even with organic and virality.

Where growth begins is where vision starts to become reality.

Growth mode enables predictability around revenue, which helps make decision-making easier, namely around capital allocation. And working capital is oxygen, especially when you’re not yet profitable. Also, growth is a magnet, which when leveraged correctly helps attract investors, employees, and customers.

Knowing where growth begins and where it doesn’t is, in my opinion, half the battle. I believe the other half is creating processes around growth experimentation, but we’ll save that for another post.